Oh, websockets.

I had trouble conceptualizing websockets and understanding how information is passed from the server to the client.

Here's the analogy I finally settled on: websockets are a lot like tossing a ball with a friend at the park.

Websockets and Balls

Pretend you're the server. You send out a message asking if anyone wants to play.

Your friend (the client) happens to hear and sends back another message, "Hell yea, I'd love to go to the park!"

This conversation is essentially opening the connection between two sockets. Now you're both listening to each other and can receive any messages sent.

But here's the deal: Because you're the server, you can play ball with multiple friends at the same time. Your friend, the client, isn't so powerful. He or she can only interact with you.

Set Up Your App

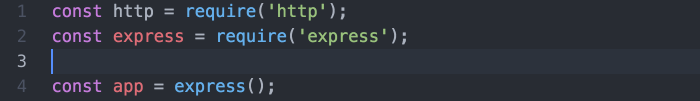

Before we dive deep into websockets, let's set up a basic Node app to work with them.

If you haven't already, make a directory and `npm init`. Work through the initial setup and then install Express: `npm i express --save`.

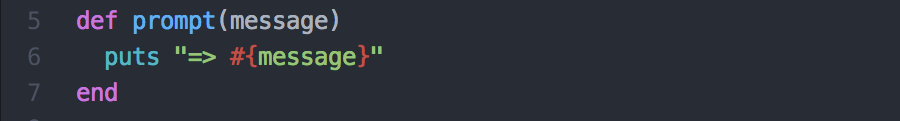

Within your app, create a server.js file.

This just requires some of the dependencies we'll be working with to get this app off the ground.

Create a folder called `public` and create a file within it called `index.html`. This will be the file we send to the client when they visit http://localhost:3000. Why 3000? Well, that's what we're setting on line 12 above. We're telling this app to listen on port 3000.

In your console, type `npm start`. Then visit http://localhost:3000 and return to the console. You should see a message: "Listening on port 3000."

Cool, huh?

Ok, now we'll get to the websockets.

We've set up the server above and now we're going to pass that variable into socketIo. (Don't worry about line 22 for now — that's for another piece of functionality.)

Now open another tab in your browser and visit http://localhost:3000. Return to your console and you should see a new message: "A user has connected. 1"

When you visited the site as a client, the server recognized the connection and notified you.

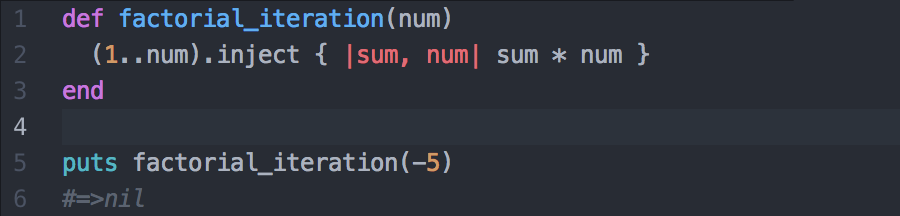

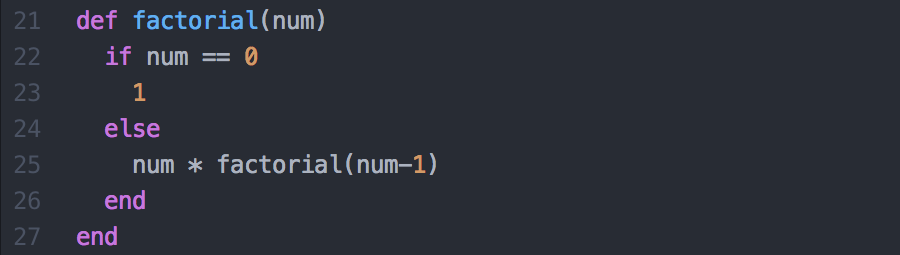

Can you guess the difference between line 27 and line 29?

`io.sockets.emit()` sends information to ALL the sockets listening on your connection.

`socket.emit()` sends information to one specific socket.

How to Work with Websockets in Real Life

Now let's build some extra features to pass information back and forth between the server and the client.

Add the following to your index.html file.

Create a client.js file in your public folder. Then add the following.

Now experiment with your connections by opening up a bunch of tabs in your browser. See how the connection count increases and decreases as you open and close tabs.

The awesome part of websockets is that they're LIVE. You don't have to refresh the page. The connection automatically updates the information based on what's happening in real time.

Got something to add about websockets? Feel free to comment below.