I didn't grow up with much. I never went hungry — my wholly unscientific litmus test of poverty — but financial security is not something I've ever experienced.

There's this moment in my memory where the scene means much less than the emotional impact. One thing I've learned is that our brains lie to us — morph memories. I was probably 14 or 15. I stood in the home of my friend, Amy. Her father was a Navy officer and tough on her. I stood in the kitchen with Amy, our friend Jill, Amy's mother and Jill's father.

We apparently couldn’t afford a hairbrush. (Laugh! This is heavy.)

I don't know what preceded the moment and I don't actually know how it played out. Sometimes, when something awful is happening, my senses dull themselves. It's as if I don't hear everything and don't see everything. Maybe our brains lie to us to protect us.

Jill's father said something. I wish I could relay the words to you now. But the implication was clear. Because I was poor, I was nothing.

I had known I was poor for many years prior to that. Children are much more adept than we give them credit. And it's hard to describe the shame you feel when you don't have money.

Especially for children, I think, because there's nothing you can really do. You're a victim of your parents' misfortune. And there's a conflict in your mind. You love them. But is it their fault you're poor?

I can't answer that question, but I can tell you this. That moment, in Amy's kitchen. The look of horror on Amy's mother's face. The feeling of my heart plummeting into my stomach. The realization that I was less than. That moment will stay with me forever.

The truth is I had a lot more than most. While we came close to homelessness, family loans kept a roof over our head. While we bankrupted, my father was able to find a job. While the car we drove was old and didn't have heat and shook like a cheap motel bed, we had a car. While food was limited, we didn't go hungry.

Anyone who's grown up without financial security knows what an impact it has on you. It's like a brand, forever imprinted on your soul. It's a hard thing to shake. Even if you have money later in life. Because the fear, the knowledge of what life is like in that situation sits on your shoulder, quietly reminding you how close we all are to the streets. Simply buying groceries without adding up the total before you get to the register is a privilege.

Assumptions

I think we all assume things we shouldn't. (Myself included. I'm no less guilty of this than anyone else.) We attempt to compare experiences — which is impossible. How do you compare hardship and pain? There's no universal measure. And this is not the oppression olympics.

I think we all owe each other a lot more grace than we give. And yet tech is small. There is gossip and cliques. How do we balance the human need to be heard and understood with our deep desire to fortify the lines between our tribes?

A Culture of Vulnerability

I've been thinking about this for some time. If you've been paying attention, you'll have noticed some of this has seeped into various talks I've given. I think if we're going to build a culture of acceptance and safety and trust, we have to build a culture of vulnerability. A safe environment where we don't have to be anything but our best selves.

And your best self varies greatly day-to-day, right? Some days my best self is more or less a titan of impossible feats. Other days I can barely manage to check email. We are not the machines we work on. We are human and broken and flawed and yet... beautiful.

I think trust is a lot like that bridge in Indiana Jones. Only the penitent man shall pass. You have to show vulnerability to receive it.

When I first mentioned this idea to James Turnbull, he offered wise counsel. How could people be comfortable sharing without recrimination? And how do you build that culture? He commented that the person first showing the vulnerability takes a huge personal and professional risk.

The Hard Truth

James is right. I wish he wasn't. But he is.

How many of us suffer from anxiety or depression and hide it? How many of us have been at the bottom of a Twitter dogpile? How many of us are scared to be our whole selves because it doesn't fit some standard prescribed by society or our small world of tech?

I guess what I've realized is that if I want this culture of vulnerability, I have to go first. And this is my attempt to be vulnerable with you. To share the parts of my story that have been obfuscated by different narratives.

Why I'm in Tech

I get this question a lot, because I have an odd background. I did not play video games in utero. I did not build a server farm from my parents' garage at 8. I did not teach myself Fortran at 15. And my story doesn't take away from those of you whose stories are classically associated with computer science. None of our stories are better or worse than the next. It's additive. Life, in many ways, is a write-only database.

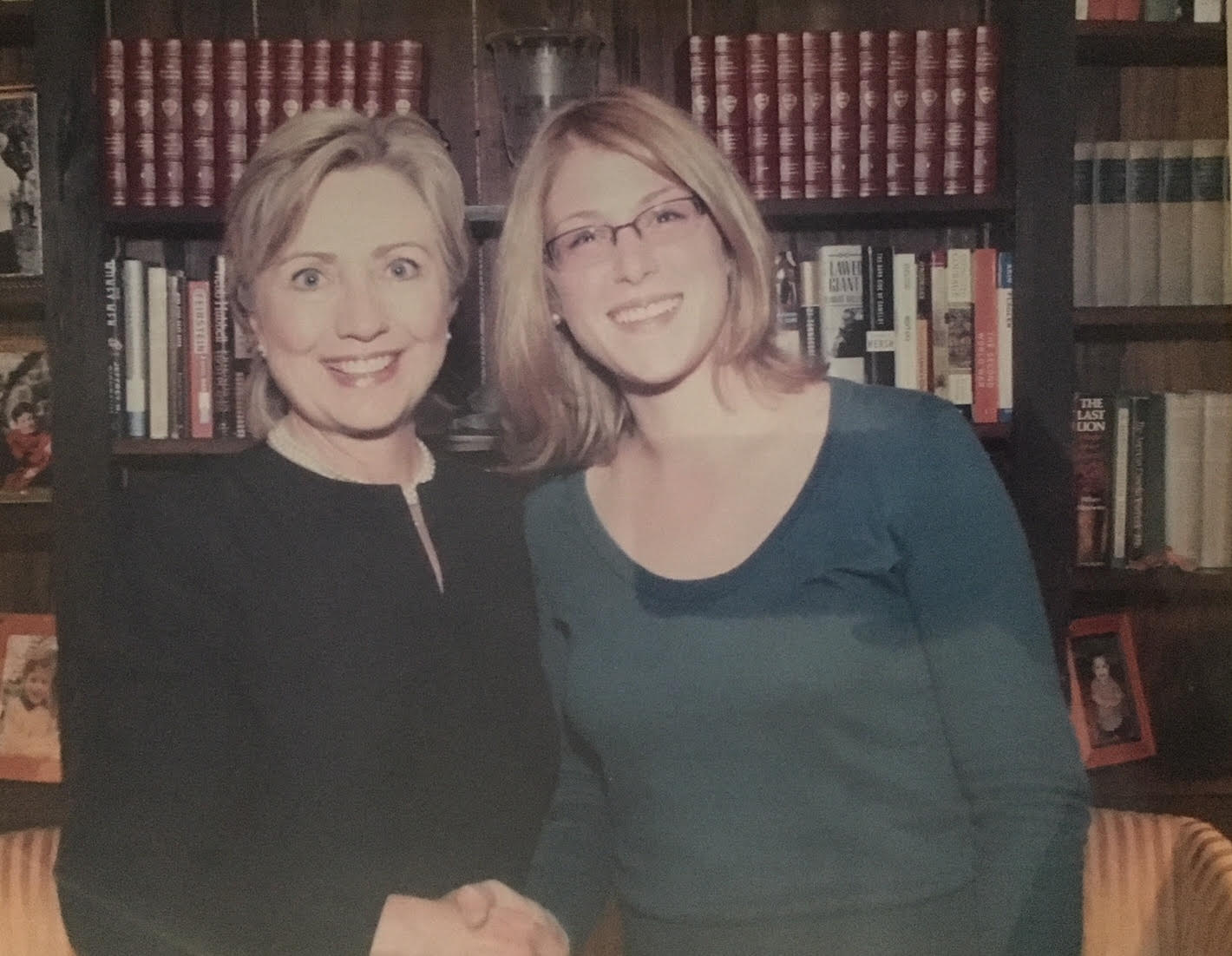

I wanted one thing as a child, and that was to be president of these United States. I know, I was a simple girl with small dreams.

My mother took this photo in the Museum of Natural History for the Washington Post.

My hero and me.

Growing up in DC infects you with a passion for politics and a deep belief in the steady effectiveness of bureaucracy. I've loved politics for as long as I've been breathing and had zero intention of doing anything with computers other than play the occasional game and chat with friends on AIM.

College

I've always been ambitious, but I worked hard in college because I had no choice. There was no money. I took out loans. I worked multiple jobs (thank you Old Navy and UCF). I did as much as I could to position myself to succeed. But, as anyone with a humanities degree will tell you, life isn't friendly to those of us who love history and words and people.

I met my (now ex-) husband at school. We were RAs in the same community. I hadn't dated much as a teenager but I always said I would marry the smartest man I met. And I did just that. He was brilliant and funny. I fell in love.

Job Hunting In The Recession

I graduated school straight into the recession, and — much to my dismay — no one gave a shit I wrote a thesis on Iran's nuclear program.

Luckily, I had taken a bunch of unpaid internships (I was busy) and had earned the trust of several influential people in Orlando. I did what I've always done, I pounded the pavement. I needed a job and surely someone needed me.

I landed a temporary gig at a PR agency. My boss could only be described a sociopath who, as a middle-aged man, lied about his ownership of the company and only hired 20-something pretty girls straight out of college. Our office had to be on the 9th floor because it was one floor higher than the competition. We couldn't bring Pepsi into the office because he only supported Coke. The man was a nutjob. I resigned from that position a week before the entire office was laid off.

My next job was only slightly better. I worked in PR and community relations for one of the largest hospitals in the country. I struggled to balance my young and naive desire to move fast with the slow churnings of a large organization. I loved my colleagues but struggled to connect with my boss. It was my second job in a row I'd had conflict with my supervisor and I began to think I was the problem. (In some ways I was. I had a lot to learn. Still do.)

When my ex-husband was offered a job in my hometown of DC, I was eager to move home. I'll never forget my last day at the hospital. The vice president came out to the elevator and asked if I was becoming a "kept woman." Bet none of you boys have been asked that.

My Time As A Housewife

We moved to DC. Into a beautiful apartment next to Key Bridge. My ex was an engineer and I could take a break from working. And then I languished.

I felt like a failure. I was clever, I had worked hard and yet there I was again — worth nothing.

I'm a big believer that people need work. Without it, we struggle to find purpose and fall into a lull of unchallenged existence. I struggled. I found work here and there as a fundraiser for small nonprofits. But I was unhappy. I was searching for a joy I couldn't find.

I tried several times to start a business with my family. That, like any entrepreneur will tell you, failed. I took art lessons. I searched for alternative careers. And I watched too much TV. I had become a kept woman after all.

Editing Emily

And then one day I received an email. A mutual friend from my PR days had recommended me to edit a self-published book for publication on Amazon. I said yes. I was trying to pay off my student loans and could use the extra money.

I undercharged and did a fairly terrible job. I'm lucky she paid me at all. But I enjoyed it. It was relatively simple work and it gave me freedom. I didn't have to show up in an office. I just did the work. And I knew I could improve.

So I kept doing it. I found more clients who had written a book, wanted to self-publish and needed help. I researched grammar. I learned how to format books for Amazon. I figured out more about the process of self-publishing. I started blogging for authors. Then a few entrepreneurs wanted me to blog for them. I liked that even more than editing — often terrible — books. (Ask me about alien smut.)

And suddenly I had a tiny business: Editing Emily. For three years I ghost wrote blogs for professional organizers, etiquette experts and tech entrepreneurs. It was an interesting client list and I learned a lot of semi-useless information — which, if you know me, comes at no surprise.

Slowly, with tons of practice, I grew into a good writer. And then a great one.

Editing Emily wasn’t anything special. I didn’t make millions and I didn’t write for big name celebrities. But I had built something out of nothing and, for that, I was proud.

My Daughter

I think this is the only photo of me pregnant on the internet. Enjoy.

My midwife, Jo, weighing my daughter.

In Spring 2014, I "felt" pregnant. My ex didn't believe me. But my body felt different. I took a test — and (not) surprise! — I was pregnant. The pregnancy was relatively easy and I had a quick home birth (about which I could talk for at least an hour so be careful I don't corner you if you ask).

Giving birth was the first time I felt truly powerful. My body felt less like something to be criticized and objectified and more like a symbol of ferocity and strength. (I recognize birth stories encompass a wide set of experiences. If you ever need to talk about yours, I am here for you.)

And then the reality of the early days of parenting hit.

My daughter at 3 months old. Look at that hair!

I didn’t know it yet, but I was suffering from a postpartum complication called postpartum thyroiditis. My pregnancy gave me Hashimoto's — autoimmune thyroiditis. I was hyperthyroid and by the time I went to the doctor several weeks later, my resting heart rate was 120. I was hot, filled with rage and wanted to die. I remember sitting in a bathtub, trying to get a moment of silence away from the endless needs of my newborn. A moment to be alone. A moment for my body to be mine and only mine once again.

I kept thinking about what it would feel like to drown. To have the water sting my lungs. To accept death. I didn’t want to commit suicide. That required action. It was too violent in some way. I simply wanted fade away. To vanish and be forgotten.

New moms need a lot of love. And if you know one, I can't tell you how much she might need you to just sit with her. Be there in the loneliness with her. Give her permission to stop pretending it's all sunshine and baby toes.

I didn't take maternity leave — one of the great mistakes of my life. (Yet very on brand.) I missed only one deadline, the day I went into labor. That sentence is ridiculous and shameful. Take your maternity and paternity leave, please. And fight for it in your workplaces.

An Ultimatum

I literally wrote articles like this.

Weeks past and it became apparent that writing while my active baby squirmed in my arms was going to be more or less impossible.

My ex-husband issued an ultimatum. I could stop working to care for my daughter full-time. Or pay for childcare out of my salary exclusively. Real partnership, right? It was one of those moments that created a typhoon of emotion for me and one he likely doesn't even remember. Words can be empty and powerful at the same time.

I made probably $35,000 a year. Far short of what I needed to pay the $2,200 per month for daycare in Arlington.

I sat on a sidewalk in Northern Virginia sobbing on the phone to my mother. I held my daughter in my lap. It was early spring. The breeze still cut through my clothes but the sun was out and enough to suppress winter’s chill.

My tiny baby was precious, as all babies are, but she was also in that phase of her life where she was completely unforgiving. Quick to scream and difficult to soothe.

I sat crying to my mother about how hard it was, how tired I was, how much I needed something — someone — to be there for me. To support me. To care for me.

In that moment I had a realization. I was wholly financially dependent on another human to survive. I couldn’t support my child and myself in DC independently. My work was admirable but not valued. At least not valued in the way an engineer was.

My Decision

And in that moment I decided this fact wasn’t acceptable. Not for me. And not for my daughter.

The last photo of my daughter and me in the room in which she was born.

I found a Ruby meetup in Arlington (I owe them so much for their kindness) and I started a class on Codecademy. A few months past and I began looking for a code school. I considered the ones in DC or NYC but everyone at Arlington Ruby said I should go to Turing, in Denver.

And that's what I did. We packed everything, I said goodbye to the room I gave birth to my daughter in and we left. My daughter was 6 months old. (Ask me about hunting down dry ice on a cross-country drive to transport breastmilk.)

That first night in Denver, I was scared. What had I done? Was this all a terrible mistake? But it didn't matter. The decision was made. And a month later, I started school.

Learning Ruby

My daughter wearing a Turing shirt and my disaster of an apartment.

I spent seven months entrenching myself in something which I had no experience in and for which I had no natural inclination. I made another decision. I wasn't going to quit. The only way I would have left Turing is if the staff had kicked me out.

And I can't tell you how powerful that was. The decision to stop saying "no" to myself. To keep pushing until some more powerful outside force stopped me. It was freeing. I took the brain capacity I would normally dedicate to worry and fear and instead dedicated it to learning.

I wasn't the most brilliant person in my class, far from it. But I live by a saying, "Hard work beats talent when talent doesn't work hard."

At some point through school I realized my previous career had been a waste. I felt like a failure. Again. In what way could writing, the one thing I knew I was good at, help me as a software developer?

I couldn't have been more wrong.

Elbowing My Way Into Tech

I worked my ass off and, knowing I needed a job, pushed hard in the final weeks to get as many interviews as I could. By some miracle, I landed four offers. Please don't mistake this for a measure of my talent as a developer. It is, more than anything, a result of knocking on dozens of doors. Of putting in the work. Something of which we are all capable.

My first technical interview not only included whiteboarding but an 8-page paper program I needed to debug. Seriously. They handed me 8 pages of printed paper and asked me to debug it. Few technical interviews scare me now because when that's your first experience, the only step forward is simply to buckle the fuck up.

The job I chose was a job in Java. The entire interview process I kept confirming they knew I didn't know the language. Not even close. But I learned. You can always learn.

A Crumbling Marriage

My relationship with my partner entered a kind of stasis while I was in school. We were two ghosts passing, talking only about our child, work and school.

When I graduated Turing, and started my first job, the crevasses between us became apparent once again.

We started marriage therapy. But repairing years of damage and hurt — initiated and felt by both sides — is hard. More than hard. Through a series of events and discoveries, it became apparent the marriage was not healthy for either of us.

I used to sit, staring at my daughter while she slept, tears quietly pooling until they broke the threshold of my eyelid and pounded the sheets. I wondered how a divorce would break her. What damage I was choosing to inflict on her. Because it was a choice. And it was my fault.

But for the first time in my life, I could afford an apartment of my own. I still wasn't sure how things would play out in the divorce so I chose a pretty shitty apartment, but it was mine nonetheless.

My First Talk

Just before I moved out, I had my first talk accepted to three conferences. Humpty Dumpty: A Story of DevOps Gone Wrong was angry-typed in a closet while pumping (I was still breastfeeding) after my third horrible interaction with the ops team at my job. I, apparently, do my best writing when I'm feeling things.

The day of my first talk, I was terribly nervous. And incredibly sick. My first audience was a group of Ukrainians. Lovely people. But they don't smile. Ever. I panicked when the display didn't work quite right, rushed through the talk and did an embarrassingly poor job.

The second audience were Swedes, not exactly the easiest to make laugh. A Swedish chuckle is equivalent to an American belly laugh. But I did make them chuckle! I moved too quickly and wasn't well paced, but my performance was pretty good.

My third time giving my first talk, Humpty Dumpty: A Story of DevOps Gone Wrong, at DevOpsDays Madison.

The third audience was DevOpsDays Madison. That conference and its organizers will forever be special to me. People thought I was funny! And it was there that I fell in love with public speaking.

It's true that I'm naturally comfortable performing as court jester to get you all to laugh and feel things. But so much of my ability to speak is my ability to write. All my talks are written, word-for-word in the notes. There are no bullet points and general direction. That works for a lot of folks. Just not me. I choose words purposefully. I select imagery intentionally. It's scripted storytelling.

Developer Relations

Like many women in tech, I began to experience some gender discrimination at my first job as a backend engineer. I was the only woman on a team of 14 and, especially as a junior, that can highlight some really shitty behavior.

After about my 8th meeting with "HR," it became woefully apparent I needed to move on and I did what I've always done, I knocked on doors. I asked folks to coffee. I let people know I was "casually looking."

Brandon West just so happened to put a note in a DevRel channel that he was about 6 weeks away from hiring a developer advocate. Two mutual friends made introductions. I met him at a stereotypically Denver coffee shop and we chatted. I summarized that meeting in the Intersection of Life + Career.

It was a great fit. I got the opportunity to write more talks and practice speaking. I learned how quickly travel can burn someone out and I deeply appreciate Brandon taking a risk on me — one I hope paid off for him as much as it did me.

Recently, Jason Hand — a close friend and one of the great advocates of my career — moved to Microsoft. And I got a message from Steve Murawski.

What's Next

Which brings me to my next role. I feel humbled and undeserving, but I'm thrilled to announce I'm joining the CDA team at Microsoft as a CloudOps Advocate.

Saying that won't get old for a looooonnnng time. The team at Microsoft has built out a phenomenal group of advocates with an extremely diverse set of skills. I simply can't believe I get to work with them.

I think in many ways Microsoft has helped legitimize Developer Relations and highlight what a phenomenal role it can play in product development.

And that's what I'm going to focus on. I want to do a lot less talking and a lot more listening. I want you to find me and reach out. Tell me what you love about what we're doing and where you think we can improve. You can even tell me where you think we absolutely suck.

I think it's important as advocates we remember that we don't talk at engineers, we speak on their behalf.

Just Keep Swimming

This tome of a blog post is a (perhaps too) verbose way of saying this: I am fundamentally not special. I'm not brilliant. I'm not particularly talented. I simply work hard. And I've been incredibly blessed with countless opportunities.

At any point along my journey, a snapshot could have painted me a failure. And yet here I am. Still standing. Still growing.

I believe kindness and hard work are worth much more than raw intelligence. I believe we, as engineers, are forming the future. We are developing systems that will make decisions for humanity. And the ethical implications of that are weighty, to say the least.

We have an opportunity to fundamentally impact our world's future. We can fight on behalf of good or — whether from maliciousness or laziness — we can allow bad actors to infect our work.

Whatever you do, don't quit

The people who lose at life are the people who quit. So just don't quit. Keep marching, even when the steps are so slow and small they're barely noticeable. Velocity is much less important than progress.

We are survivors. All of us. We have suffered and overcome. We have survived divorces, deaths, depression, cancer, rejection, racism, sexism, homophobia. We have had doors slammed in our faces. We have had our hearts broken. We have trusted. And been betrayed.

But we are still walking. And together, we are a tribe. A tribe of survivors. With the scars to prove it. In every scar lies a story. A story of resiliency.

I have survived — thrived — in large part because of this community. This loving, hopeful, wonderful community.

And I wonder sometimes what our workplaces would look like if we could build a culture of vulnerability. A culture of raw truth. A place free of judgement. A place safe to cry. A place where mistakes were forgiven quickly and without the whispers of gossip.

My ask is this. That you never quit. That you give vulnerability freely and you accept the vulnerability of others with grace and love. That we support each other.

This community is small. But we are mighty. And I wonder how much more powerful we’d be — how much better our engineered solutions would be — if we dropped the facades of our Instagram accounts and practiced acceptance. Of ourselves and of others.

THANK YOU

Thank you for being my light in the dark. Thank you for dragging me through the tough times with your notes of encouragement, your GIFs and your jokes. You have brought me laughter in the midst of tears.

And I only hope I can be a source of joy and encouragement for you. That I can use my voice to speak for you. To drive our industry and our culture forward. To represent you. And, ultimately, to tell your stories.